Giving blood saved my life

Alan Jasper has given blood more than 80 times. But when a low haemoglobin level last year meant he couldn’t donate, it led to a diagnosis that ultimately saved his life.

I first became interested in blood when I was in primary school. My father had always worked in manual labour and in case he suffered an accident at work he wore a fob attached to his belt with his blood group on it: A negative, which is in fact my group, not that I knew it at the time!

I first became interested in blood when I was in primary school. My father had always worked in manual labour and in case he suffered an accident at work he wore a fob attached to his belt with his blood group on it: A negative, which is in fact my group, not that I knew it at the time!

Jump ahead to my first term as an undergraduate at the University of Manchester in 1986. There was a big drive to encourage blood donation, with one of the main halls converted to a donation centre for the week. I felt a bit of public duty to do it, so duly volunteered. I felt a little bit of trepidation, but it all went smoothly, although it was quite different to nowadays - lots of camp beds and only a doctor could insert the actual needle!

I donated regularly throughout my time in Manchester and then continued when I began as a maths teacher in Shropshire. My school hall was used for donations during half-term breaks.

(Picture: Alan at his desk in his school office)

As my career progressed, half-terms were not always convenient and so, with the advent of online booking, I began to use the donation centre on New Street in the centre of Birmingham and would make a day of it. I would quite often go on the train and have a tasty lunch and do some shopping in town.

I have always been interested in numbers, logic and reasoning so it was no real surprise that I read mathematics at university. I was the first person in my family to attend university and I stayed on for a further year to do my postgraduate in education. I am also Chartered Mathematician (C. Math) and despite becoming a deputy headteacher in 2005 and a headteacher ten years later, I never stopped teaching mathematics in school.

I have always been interested in numbers, logic and reasoning so it was no real surprise that I read mathematics at university. I was the first person in my family to attend university and I stayed on for a further year to do my postgraduate in education. I am also Chartered Mathematician (C. Math) and despite becoming a deputy headteacher in 2005 and a headteacher ten years later, I never stopped teaching mathematics in school.

I have also always been an avid sport fan and have been a season-ticket holder at Aston Villa for 30 years. I enjoy all music, theatre, opera, and ballet and regularly spend time in London where I can also indulge my passion for history and science at the same time. Even though I have now retired, I am in my fifth year as Chair of the Governing Board at a Primary School in Wolverhampton, and I am about to begin my third term as the President of my Rotary Club, both of which I am deeply passionate about.

(Picture: Alan and his brother David at the London 2012 Olympics during David's first remission)

Although I initially gave blood out of a sense of public duty, I began to realise just how important it was.

In particular, I learned the uses of my blood group. A negative red blood cells can be given to around 40 per cent of the population. A negative platelets can be used to treat people with any blood type and are most commonly needed by hospitals when treating patients with blood cancers, so it is always in demand. This really hit home ten years ago when my younger brother, David, was diagnosed with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma – a blood cancer. He was treated over a five-year period and needed numerous blood and platelet transfusions.

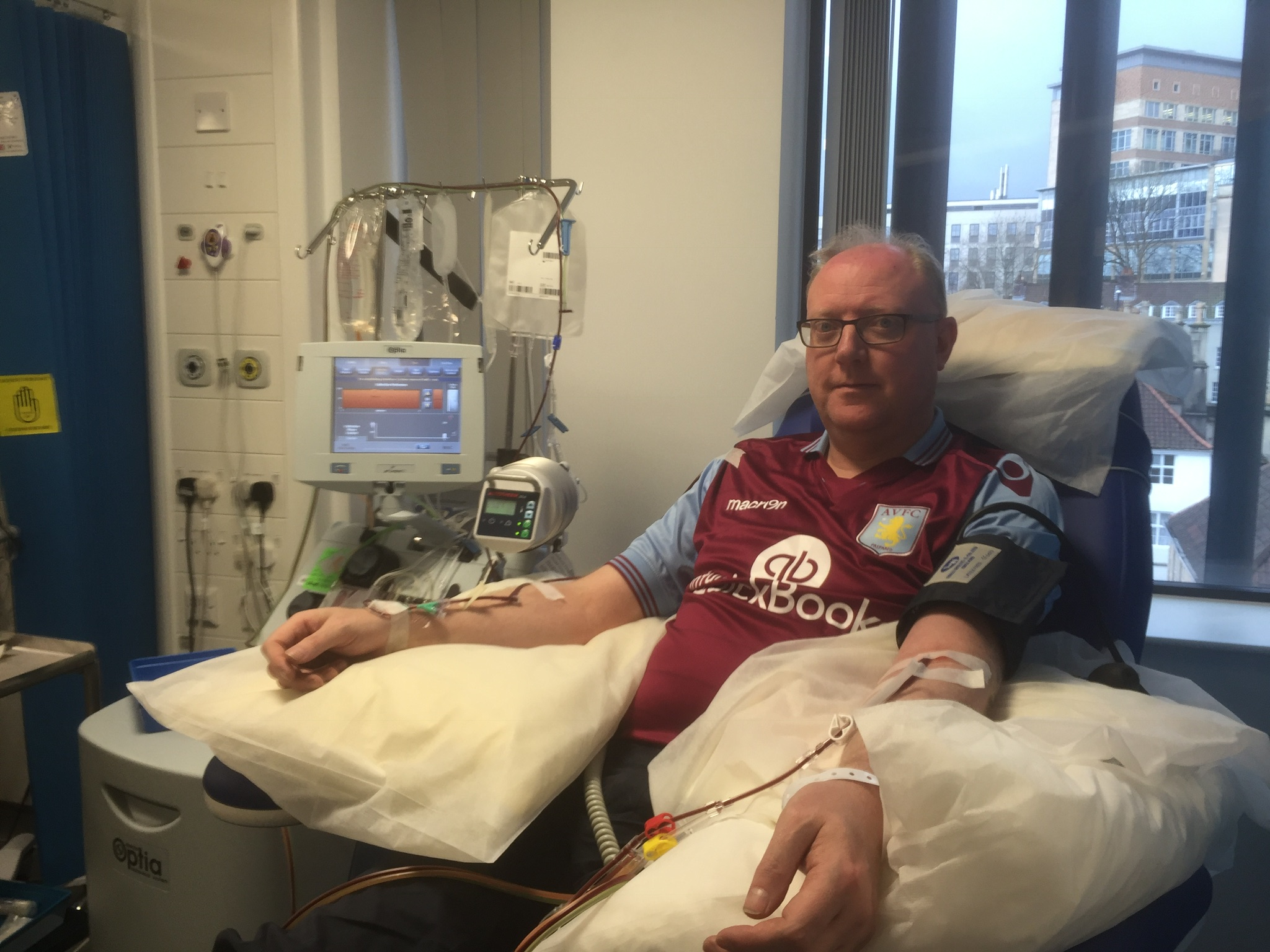

David had two periods of remission, but when his cancer returned for a third time the only prospect of a cure was a stem cell transplant. I volunteered and was found to be a perfect match; siblings have a 1 in 4 chance of this being the case. In autumn 2015, I spent a day at Bristol Royal Infirmary donating my stem cells. The very next day I was there, with David’s wife, when he received them. The transplant was a success and he no longer had blood cancer. I also donated some of my T-cells to him later in the year as part of a trial to help boost his immune system. Unfortunately, nine months later he caught pneumonia and was unable to fight it off and so sadly passed away. However, up until a week before he died, he had that vital commodity called “hope” which he would never have had without his various treatments.

David had two periods of remission, but when his cancer returned for a third time the only prospect of a cure was a stem cell transplant. I volunteered and was found to be a perfect match; siblings have a 1 in 4 chance of this being the case. In autumn 2015, I spent a day at Bristol Royal Infirmary donating my stem cells. The very next day I was there, with David’s wife, when he received them. The transplant was a success and he no longer had blood cancer. I also donated some of my T-cells to him later in the year as part of a trial to help boost his immune system. Unfortunately, nine months later he caught pneumonia and was unable to fight it off and so sadly passed away. However, up until a week before he died, he had that vital commodity called “hope” which he would never have had without his various treatments.

(Picture: Alan at Bristol Royal Infirmary donating stem cells)

In February 2020 I went to my usual venue, Birmingham Donor Centre, to give blood. My haemoglobin level was 133g/l which is very slightly below the required 135g/l. I was told not to worry as this seemed to be a one-off. I was given a leaflet regarding dietary advice and was told to wait three months before donating again. I felt absolutely fine and had been walking 5-10 miles a day since retiring only a few months previously. I actually felt I had let people down as well as taking up a valuable donation appointment!

I had given blood 80+ times before without a problem!

I had given blood 80+ times before without a problem!

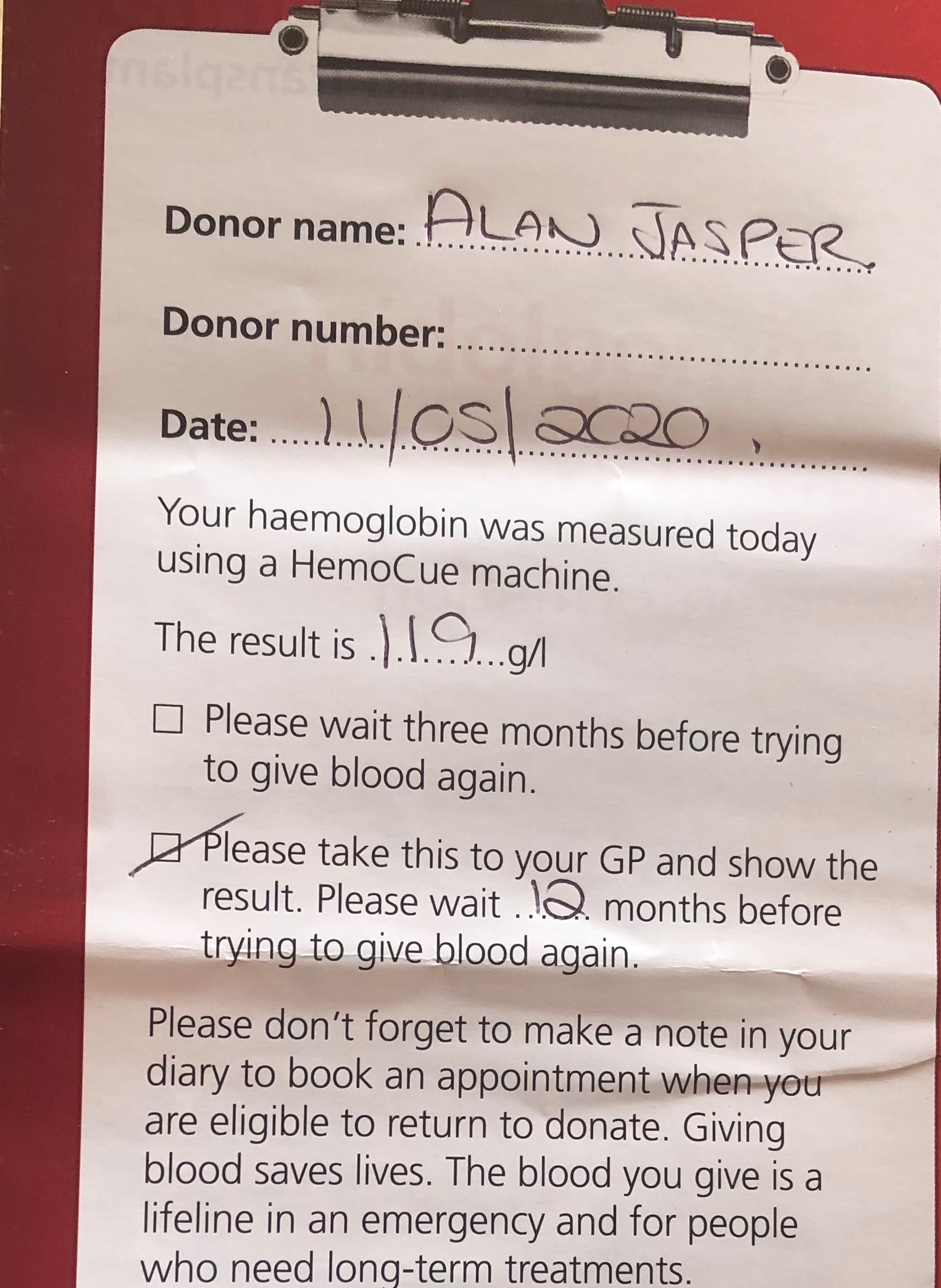

As the pandemic took hold, I was very keen to donate again and so went back as soon as I was allowed to. On 11th May 2020 my haemoglobin level was 119g/l and I was told I had signs of anaemia. This was found during the normal pre-donation checks. I had a chat with the nurse present at the session and I was strongly recommended to seek advice from my GP and get a formal blood test to determine the reasons behind it. I had no symptoms and was seemingly in very good health. I made a doctor’s appointment the next day and I had a blood test later that week. I was then referred to a consultant and soon began a series of tests and procedures almost on a weekly basis.

(Picture: Alan's referral note)

Despite still having no obvious symptoms, I began a series of hospital tests which ultimately resulted in the early diagnosis of an aggressive and potentially life-threatening form of oesophageal cancer and the successful treatment that followed.

I was diagnosed in July and by September I had met another consultant and an oncologist, and I began two months of intensive chemotherapy in September. In December I had an 8-hour operation to remove my oesophagus. This was successful and in January I received the news I was cancer-free and required no more chemotherapy.

I am completely indebted to the nurse who asked for my referral, as my chances of recovery would have been considerably reduced if I had waited until I had developed symptoms, in my case, an inability to swallow.

Like Alan’s brother, there are many people who need blood and platelet transfusions as part of emergency or ongoing treatment for a variety of conditions. Your donations make these treatments possible.

To ensure it is safe for you give blood, your haemoglobin levels are always checked before you donate. The acceptable levels for donating are set quite high so that you maintain safe levels of haemoglobin after giving blood. It is important to remember that haemoglobin levels vary from person to person and that slightly low haemoglobin can be normal for some people and does not always mean you are ill.