Rare blood: the facts

When many donors first find out what blood type they have, the first question they ask is, how rare is that? For most, the answer is not particularly – and that’s no bad thing – but for a very select few, their blood group is literally one in a million.

What does it mean to have a rare blood group, though, at a time where hospital demand for it is rising?

Let’s start at the beginning:

What is a blood group?

Blood groups are determined by the antigens (or markers) and antibodies that are present or absent in the blood. Antigens are protein molecules found on the surface of red blood cells and antibodies are protein molecules located in the blood plasma.

The different types and combinations of these molecules give us our blood type – A, B, AB or O – as well as your Rh D factor (+ or -).

Antibodies are produced in response to antigens (markers) that the body does not recognise. This includes when a patient is exposed to antigens via a blood transfusion: they produce antibodies to counteract them.

Once a patient has developed an antibody, they need blood that is negative for the corresponding antigen to avoid a transfusion reaction. Ideally, all patients should receive fully matched blood so that they don’t develop an antibody.

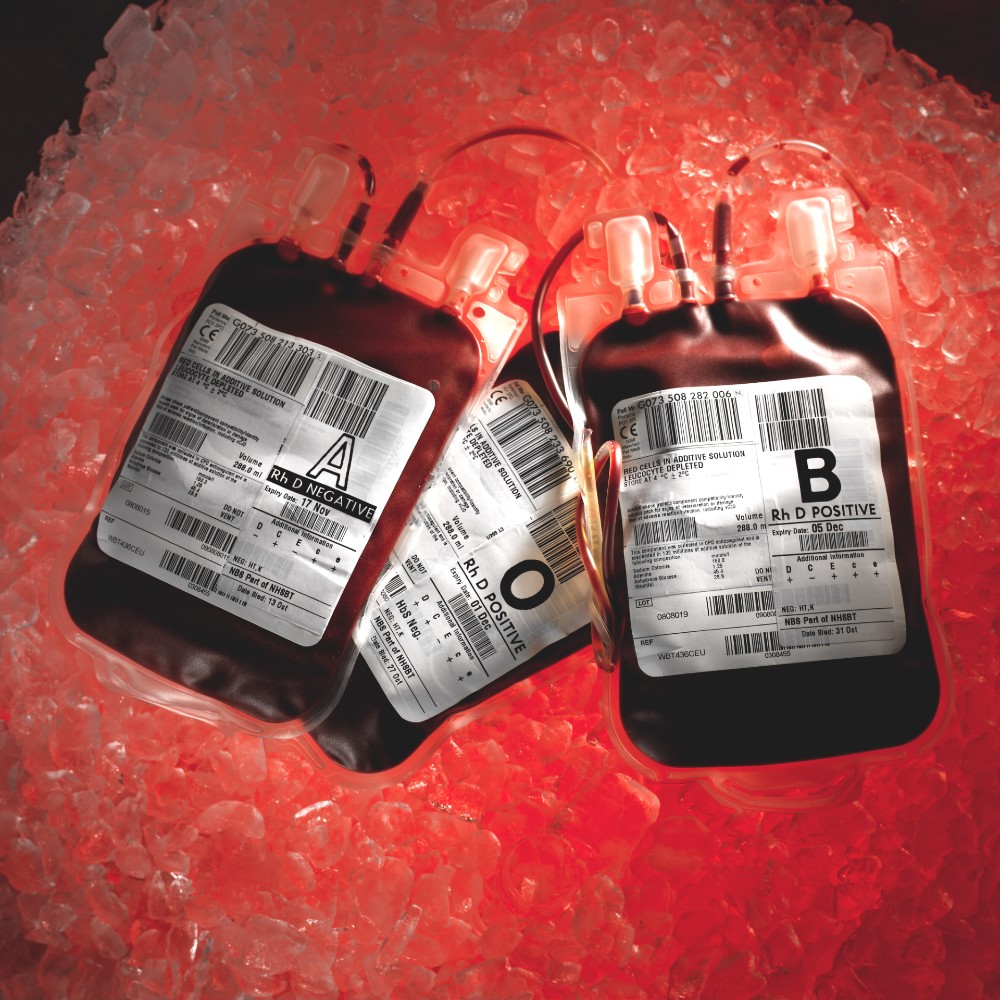

Rare blood types

For most of us, matching the ABO groups is generally straightforward. However, there are not just ABO antigens on the red cells – in fact, there are over 360 different antigens that we know of.

When the red cells have some of the antigens that are not commonly found in the general donor population, or lack specific antigens that most of us have, the blood is classed as ‘rare’.

The UK definition of a rare blood type is one that occurs at a frequency of 1 in 1,000 of the population or less.

Sometimes the blood type is so rare that we don’t have any suitably matched blood in stock. We need to search the database for donors with the same matching type and ask those individual donors to come and donate.

For some of the rarest blood types, we have only a handful of donors.

Blood is used to help patients in many different clinical situations and rare blood is no exception. Although red cells from a blood donation have a shelf life of 35 days, we often freeze some rarer donations to ensure they are available for urgent requests.

Sickle cell disease and the Ro subtype

Sickle cell disease is an inherited condition that leads to abnormally shaped red blood cells. These abnormal, sickle-shaped cells can block blood vessels, causing severe pain known as a crisis and possibly leading to health complications including stroke.

The effects of sickle cell disease can be managed with regular blood transfusions or red cell exchanges. Patients who need regular transfusions require blood that matches their own type. Otherwise, they could suffer a transfusion reaction.

There are 15,000 people in the UK living with sickle cell disease, most commonly those of African or Caribbean descent. Because the best blood matches come from donors of similar ethnic background, more donors are needed from African and Caribbean ethnic backgrounds to help treat those with sickle cell disease.

Ro is a blood subtype that is also found most often in people of African or Caribbean descent, so it is more common in people with sickle cell disease and, in England, there has been an 80 per cent rise in demand for Ro blood over the last three years.

With around just two per cent of donors having Ro blood, though, meeting hospital demand can be difficult.

Read about Ezrah's story.

Rare blood moves around the world

Although the majority of requests that we receive for rare blood come from hospitals in England, they can come from any country in the world, too.

International collaboration is needed to collect the donations and manage the logistics of supply. During the past two years we have provided rare blood for many different countries, including Sweden, Poland, Finland, Ireland and the USA. We also receive rare blood from overseas to treat UK patients who can't be matched here.

Read about Zainab's story

Many of the requests that we receive for rare blood are to help patients who need regular blood transfusions. The more transfusions a patient receives, the greater the chance is that they will develop antibodies to antigens on donor red cells. This makes it more difficult to find suitably matched blood for future transfusions.

Meeting the demand for rare blood types is logistically challenging and often time-critical. Teamwork is crucial to move these precious donations to where they are needed. But it all depends on you – blood donors responding to our calls, texts and emails – so, thank you for helping to save and improve patients’ lives.