The journey of blood - at the hospital

Blood donation in its simplest form is a beautiful thing: people take time out of their day to give blood for patients who need it.

In reality, though, it’s far more complex.

The journey starts even before any of your blood is taken. It involves teams of people, fleets of vehicles and some fascinating science.

It ends when the patient receives your blood, and you get a text message telling you where your blood has gone.

Here, Fatts Chowdhury, Consultant Haematologist at Imperial College Healthcare Trust and NHS Blood and Transplant, takes us through how blood products are used in hospitals.

St Mary’s Hospital is one of four major trauma centres in London. Stocks of blood are slightly harder to manage here because it is essential that we have enough for all our routine and emergency surgeries and especially our trauma patients who are brought to us in an unpredictable manner.

The unpredictability of trauma victims needing blood means that we have to ensure we have extra blood or can obtain extra blood at very short notice. We try and keep enough stock in our fridges for at least three to four days’ supply, ordering more as needed, if stocks are used up rapidly. The blood units have a shelf-life of 35 days from the time of donation, but this may be less depending on when they have come to us from NHS Blood and Transplant.

It can be hard to predict what blood you will need for every speciality, but we are always ready

Our aim is to minimise blood product usage as we recognise the commitment and generosity of donors. As part of the national patient blood management initiative, we will do things like testing patients iron levels before surgery, so that if this is found to be low we can prescribe oral or intravenous iron infusion to treat patients. Otherwise, in case of emergencies or if the patient is clinical very unwell, we use blood transfusions. Testing and treating iron deficiency before surgery has allowed us to reduce blood transfusions. This also has an positive effect on the patient’s wellbeing after surgery.

At St Mary’s Hospital, the radiology department has expanded its technical abilities, enabling it to undertake procedures that were previously only possible using surgeons. This allows patients to have procedures in the radiology department under x-ray, ultrasound or CT guidance, which is less invasive than having open surgery.

Rare blood group

The Jehovah’s Witness community has taught us a lot about how you can do procedures without needing to transfuse. This involves thinking and planning in advance, which can be challenging, but it has reduced our overall need for blood. We’ve had trauma patients who are Jehovah’s Witness and we’ve been able to treat them and get them home using iron, other haematinics and medications.

It can be hard to predict what blood you will need for every speciality, but we are always ready. A maternity patient, for example, may have a rare blood group or antibody and deliver earlier than expected. The transfusion team works with the maternity team to co-ordinate care of the patient.

We make sure we have a plan for delivery, or other procedures, so that even if it is a very rare type, we have blood available and the patient gets the best treatment possible. Occasionally, we have needed to obtain very rare blood from the frozen blood bank at very short notice. Pre-planning is absolutely key. We prefer to plan and be ready for all eventualities so that we are not trying to arrange these things in the heat of the moment, but occasionally this cannot be avoided.

Blood use is also minimised using a medicine called tranexamic acid, which is really useful for controlling bleeding in patients. My surgical colleagues are constantly striving to develop newer techniques which are less invasive and try to use blood saving equipment more frequently. Many surgeons use what they fondly refer to as a ‘firestick’ – a diathermy knife which seals blood vessels with heat as it cuts. There is also another process called cell salvage, where we collect, wash, and return blood lost from the patient, either during or immediately after the surgery.

Similarly, we work on getting as much as we can out of platelets and plasma. As a major trauma centre, we need a certain number of platelets available at any time, but before units reach the end of their shelf-life, we rotate them to other sites – if they haven’t been used for trauma patients, they can be used at Hammersmith Hospital for patients having chemotherapy.

We also have fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and fibrinogen concentrate that can stop bleeding, reducing the need for as much blood. Like fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate has to be defrosted but fibrinogen concentrate is not frozen – it just needs mixing up, and can be used quickly to stop bleeding much faster.

Blood is stored in the fridge at 4°C. In an emergency, such as trauma, transfusions will need to be given quickly, so we use blood warmers in A&E, warming the blood up before it goes into the patient. It is important to ensure the patient doesn’t become hypothermic as it increases bleeding and can cause other problems.

Pregnant women

A&E departments will always have a mixture of O positive and O negative in their fridges. At St Mary’s, we keep a ratio of 2:1, because 80 per cent of trauma patients are men. We use O negative blood for those patients who cannot have other groups and patients who are of child-bearing age.

We work hard to give patients the best outcomes we can. With transfusions, that always starts with donors, though.

We always give women of child-bearing age O negative blood so that they do not develop antibodies that may harm the foetus/baby as a result of haemolytic disease of the foetus/newborn – a condition where the blood cells of the foetus/newborn blood cells are destroyed by the antibody so that they become severely anaemic. We keep O negative blood in the in the fridges of labour wards for emergencies for that reason.

O negative blood is also used to substitute for rarer blood types.

At Hammersmith Hospital, my haematology colleagues look after patients with blood cancer, patients needing bone marrow transplants and those with sickle cell disorder. Patients having transplants and those with blood cancers often need blood transfusion and it can be as frequent as daily if they are having chemotherapy. Sickle cell patients are treated with blood when they are unwell having a sickle crisis or when they are being prepared for surgery.

More Ro donors needed

It is not uncommon for sickle cell patients to have multiple antibodies or rare blood groups. At St Mary’s, my paediatric colleagues look after children needing bone marrow transplants for a number of different conditions, including sickle cell disorder and thalassemia.

Some of these patients will also have antibodies or rare blood groups. I’m able to help them source the required blood products from NHS Blood and Transplant, even when they are rare, by communicating with my colleagues in other departments there to find blood in the National Frozen Blood Bank, or by asking colleagues in the donor team to call in individual donors who have rare blood types to donate especially.

We frequently use O negative blood for patients who have the Ro subtype, which is why more Ro blood donors are needed. This is mainly for patients with sickle cell disorder.

Sickle cell patients may be on a regular exchange programme to keep them well. Doctors and nurses looking after these patients will inform the blood transfusion laboratory what day the patient is attending and how many units of blood will be needed.

Sickle cell patients may be on a regular exchange programme to keep them well. Doctors and nurses looking after these patients will inform the blood transfusion laboratory what day the patient is attending and how many units of blood will be needed.

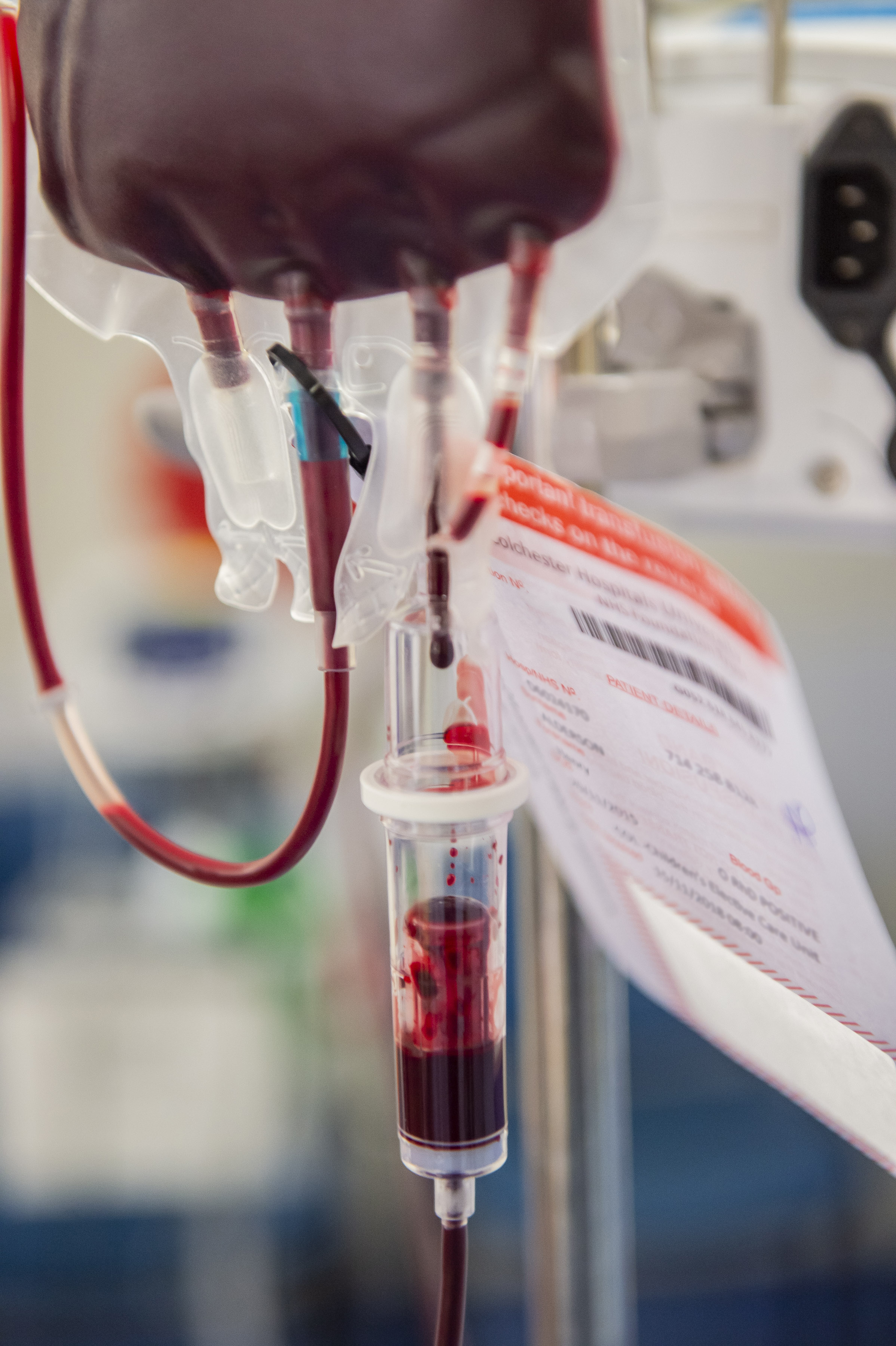

(Picture: A blood bag during transfusion)

The laboratory team will place the order into NHS Blood and Transplant a few days in advance, especially if the patient has rare antibodies or a rare blood group, to ensure that blood is available on the day of the procedure. This often needs a lot of co-ordination between the laboratory and clinical staff.

Patients sometimes come in overnight with conditions that need big operations. My surgical colleagues are able to contact the laboratory day or night to request the blood they need. If it’s a particularly complicated case that needs large volumes of blood, we can order it in for them specifically. Sometimes we need to request blood to be delivered to us via a blue light delivery from NHS Blood and Transplant.

In an emergency, like with an unusual blood group, the surgeons or the laboratory staff contact me and I will give advice on which blood is compatible and what can be substituted. The laboratory often has something on the shelf they can give.

Blood products are collected from the laboratory by porters, who have been trained to collect and deliver blood products by our transfusion practitioners. Occasionally a doctor or a nurse will collect them, but part of my job is to make sure that protocols are adhered to, across all of our sites. Training is an important part of that.

Safety is paramount. Every hospital has different policies, but we will take two blood samples to make sure they are taken from the right patient and correctly labelled. The labels have barcodes, enabling the laboratory staff to make sure blood products are exactly what the bags say they are. It is a legal requirement that we know the journey of every unit – from the arm of the donor into the arm of a patient. The blood transfusion laboratory will keep this information for 30 years.

We work hard to give patients the best outcomes we can. With transfusions, that always starts with donors, though. It’s a pleasure to work at the end of a journey that starts from such a generous and compassionate place.

Before you donate

The journey starts even before any of your blood is taken. There are a lot of jobs to carry out behind the scenes before any donors come through the door.

The journey starts even before any of your blood is taken. There are a lot of jobs to carry out behind the scenes before any donors come through the door.